China was the most disaster-affected country in 2014, with drought, storms and flooding affecting more than 58 million people and economic damages of 23.17 billion US $.

Between July 2011 and mid-2012, a severe drought was experienced in the horn of Africa. It ramped up a chronic livelihoods crisis to a tipping point of potential disaster by putting extreme pressure on food prices, livestock survival, and water and food availability. Earmarked as the worst drought in 60 years, the estimated death toll was 260,000 people. The drought directly affected over 13 million people in Kenya, Somalia, Ethiopia and Djibouti.

Unofficially known as ‘Superstorm Sandy’, hurricane Sandy was the deadliest and most destructive hurricane of the 2012 Atlantic hurricane and the second costliest cyclone to hit since 1900. Estimated damage of over 50 Billion US $, an amount surpassed only by Hurricane Katrina. It is clear that the economic costs of disaster remain both significant and worrisome for the countries and areas impacted [Vorhies, 2012]. The total number of disaster events and related economic and humanitarian losses have been increasing steadily since the 1980s.

Economic losses from extreme weather events are now in the range of $150–$200 billion annually, with an increasing share of damages located in rapidly growing urban areas in low and middle income countries. However, despite widespread awareness of these rising losses, investment in ex-ante disaster risk management (DRM) remains relatively low [Tanner, et al, 2015].

In March 2012, the Global Humanitarian Assistance (GHA) programme published ‘Disaster risk reduction: Spending where it should count’, which examined the levels of donor investment in disaster risk reduction (DRR). The report found that despite the rhetoric, just 1% (US$3.7 billion) of total Official Development Assistance (ODA) had been spent on DRR in 40 of the world’s poorest and most disaster-affected countries.

While most donors seem to agree that financing measures to reduce risk can lessen impact, quicken recovery and result in lower levels of assistance, there is continuing uncertainty as to whether this is happening in practice. Despite the positive inroads made since the Hyogo Framework in 2005 in terms of promoting DRR on the global agenda, there still appears to be a gap between rhetoric and policy recognition on the one hand, and action and investment on the other. Tracking DRR within international ODA is complex. Volumes of ODA funds invested in DRR are very difficult to track and assess, and data on financing for DRR is poor. Quantifying the total amount spent on DRR is difficult. DRR activities are commonly tucked within wider programmes and projects, including those relating to food security, health systems, and environmental management. Because DRR projects have emerged relatively recently, the data on DRR funding is limited and donors are still unsure how to report it. Current donor reporting methods therefore fail to capture adequately the full nature and extent of financing for DRR, and it is only on the basis of this limited data that we are currently able to examine donor commitments to financing DRR.

“Reducing disaster risk should not be seen as an additional expenditure, but rather an investment for a safer and more resilient world. It is about ensuring that our investments in development are not washed away when the next flood or tsunami occurs.”

Kevin M. Cahill, M.D .More with less: Disasters in an era of diminishing resources

Governments renewed their commitment to investing in disaster risk reduction at the June 2012 Rio+20 Conference. The Rio+20 outcome document, ‘The Future We Want’, invites governments at all levels to commit to adequate, timely and predictable resources for disaster risk reduction. It also calls for disaster risk reduction and the building of resilience to disasters to be addressed with a renewed sense of urgency in the context of sustainable development and poverty eradication and, as appropriate, to be integrated into policies, plans, programmes and budgets at all levels and considered within relevant future frameworks.”

The June 2012 Rio+20 Conference set the pace for the inclusion of investing in disaster risk reduction for resilience in the current post 2015 DRR Framework. The Sendai Framework sets out investing in disaster risk reduction as the third priority in reducing disaster risk for resilience. It also enumerates seven agreed global targets that include reducing direct disaster economic loss in relation to global gross domestic product (GDP) by 2030.

What then is the role of the State?

To discharge their leadership and stewardship responsibilities effectively, governments need to express this commitment through strategically and adequately resourced actions. Therefore, a committed political leadership should also facilitate the mobilization of resource investment by communities and the private sector in disaster risk reduction. This partly depends on promoting other forms of resourcing disaster risk reduction, such as insurance and micro-finance [Africa Regional Strategy for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2004].

For decades, Japan has been assisting countries in Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) by sharing its own experiences, from having been affected by disasters. Japan in the recent years has experienced unprecedented disasters, including the Kobe Earthquake (1995) and East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami (2011). Japan’s long history of fighting disasters has built some of the world’s leading science and technology in DRR. While Japan is known more for its infrastructural and technical measures, there is also an extensive knowledge base in non-structural DRR measures, including institutional building, end-to-end early warning systems, DRR education and community-based DRR.

The resourcing of disaster risk reduction is a shared responsibility between the State and other stakeholders. To facilitate this increased resourcing commitment, both political leaders and investors need to be convinced of the developmental benefits of investing in disaster risk reduction. This requires demonstrating the cost-benefit of investment in reducing disaster risks [Africa Regional Strategy for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2004].

For long, the corporate sector had been viewed as a separate entity perennially ranged at the other end of the spectrum vis-à-vis the society. Over the past few decades, this perception has undergone a complete metamorphosis and the existence of corporate sector is today intimately intertwined with the safety and well-being of the society. Rather the community today is the very raison d’etre of its being. It is the crux lending credence and substance to the world view of the corporates. The corporate sector and the society are being seen as complementary to each other – heavily dependent upon each other for mutual existence and prosperity. Through their CSR programs, corporate organizations can invest in disaster risk reduction by building capacity on DRR, sponsoring DRR training curricula, this mandate clearly links investments in disaster risk reduction to the broader objectives of sustainable development and poverty eradication.

Incidentally, investing in disaster risk reduction as the Sendai Framework explains, includes monetary investment but is so much more. Policy investments need to be made through the implementation of disaster risk reduction strategies, policies, plans, laws and regulations in all relevant sectors. Other than the guiding principles set in the formative frameworks globally and regionally, states should have national disaster plans as well as mainstream disaster risk assessments into the states vital aspects such as peace & security, health, transport, agriculture and climate change. This is why Investments are part of the five-element framework we are exploring here at LDRI on effective resilience building programs in Africa.

The adverse impacts of climate change and extreme weather events are a severe threat to livelihoods, and hold back growth and sustainable development [Tanner, et al, 2015]. The global costs of disasters are generally in the billions of US dollars per annum and rising. Chanelling investments into the DRR pool is not only necessary but a si ni qua non towards resilience building.

“The challenge, therefore, is moving from these compelling words to tangible and life changing action.”

Margareta Wahlstrom, UN Secretary General’s Special Representative for DRR, 2012

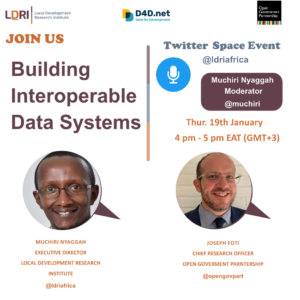

Image source: Muchiri Nyaggah, License: CC-BY